Civil society fills the crime-fighting vacuum

Published on January 6, 2021

What motivates civil society and the media in Serbia and Montenegro to work against crime and corruption, and what are they doing to fight illicit activities? The Resilience Fund supports seven civil-society and media organizations in these countries to prevent and fight illicit activities in a progressively restrictive civic space.

In 2020, 90 journalists from Serbia and Montenegro faced threats and almost 90 activists from Serbia have been attacked and pressurized by the authorities. The Serbian money-laundering prevention office initiated an investigation into 20 individuals and 37 civil society organizations for possible money laundering and terrorist financing, which was perceived as an act of intimidation. And a new law in Montenegro forces journalists to reveal their sources in the name of ‘national security’.

The space for civil society activity and media reporting in these two Balkans countries is shrinking and actors are increasingly under pressure. Despite the good work they carry out, persistent attacks and threats, together with non-responsive official authorities, limit the scope and reach of these organizations. Paradoxically, Serbia and Montenegro have aspirations to join the EU, which upholds the role of civil society and the media, considering them essential elements in defending fundamental values of human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law.

For more than two decades, civil society in both these countries has played a vital role in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy building. Civil society organizations were a driving force of anti-war protests in the 1990s and, later, the collapse of repressive state regimes. Yet, ironically, civil society activists and journalists today are labelled as domestic traitors or foreign mercenaries by tabloid media and politicians because of the critical stance they take against the authorities in the democratic order.

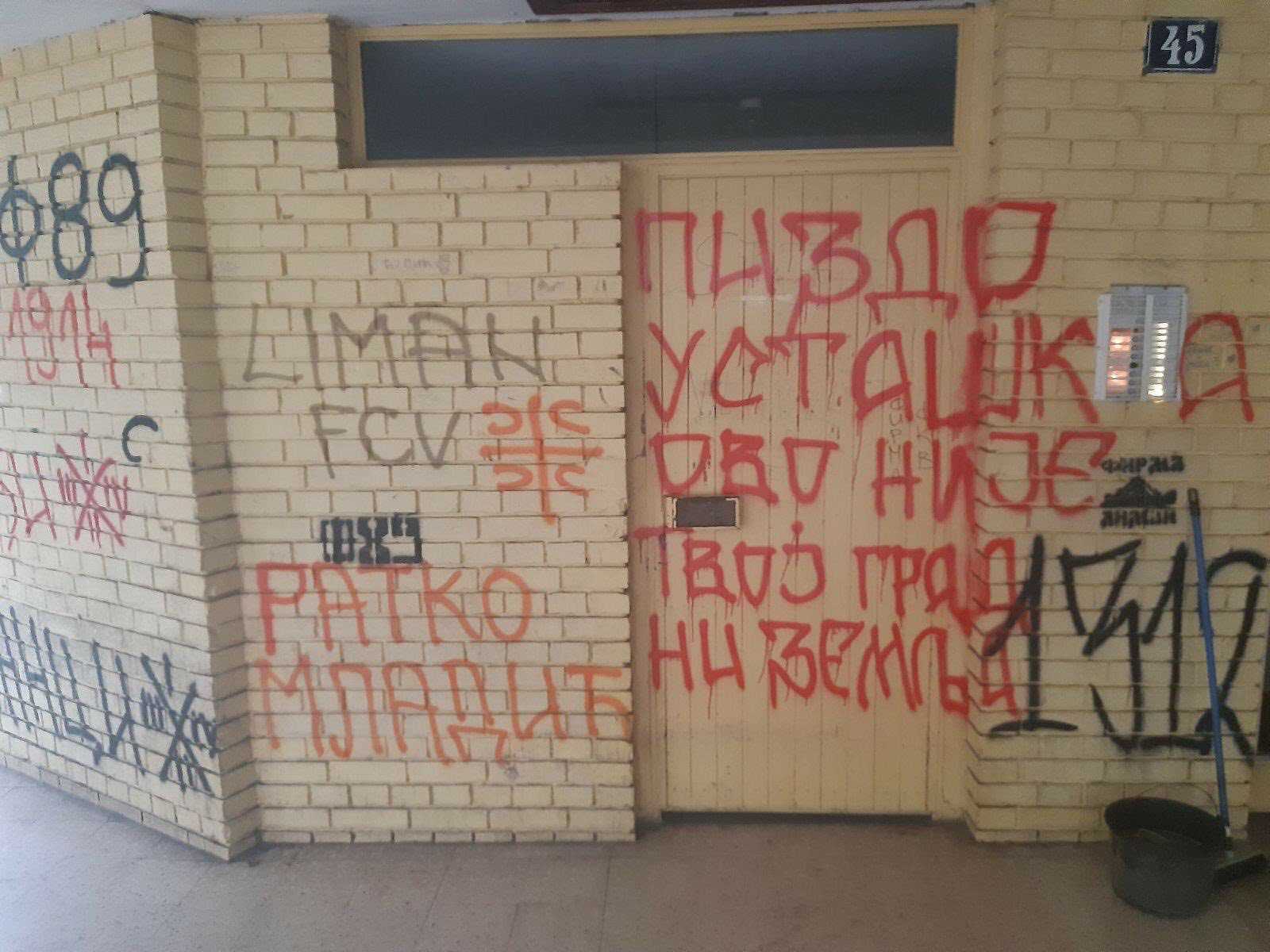

Activists and journalists find themselves as regular targets of smear campaigns. One of the latest victims is Dinko Gruhonjic, editor-in-chief of the Vojvodina Investigative and Analytical Centre (VOICE) – one of the organizations supported by the Resilience Fund – whose building in Novi Sad, Serbia, was sprayed with hate-speech graffiti.

VOICE is investigating links between political parties and private companies, especially in smaller communities off the radar of larger media outlets, and where people are eager for quality media content. In one recent story, VOICE revealed how a company owned by an ex-member of the ruling party signed 2 million euros’ worth of contracts with local institutions, in what may be a misuse of public funds.

The Association of Professional Journalists and Mladiinfo, two civil-society organizations in Montenegro, share similar objectives to those of VOICE. They believe that quality investigative journalism can uncover the truth about how public funds are misused and how organized crime has a detrimental impact on society. The Resilience Fund supports their efforts to nurture journalists: through workshops, the Fund has trained more than 15 journalists and young people who want to investigate corruption and human trafficking.

We want to empower young people to think critically, identify local community problems and influence their solutions. Through training, students learn to research, ask questions and practise journalism. They gain concrete knowledge that will be important to them even after the end of the project.

Mila Radulovic, from the Association of Professional Journalists, became motivated to organize journalistic training through what she sees as the poor institutional results in fighting human trafficking and the way in which trafficked victims are neglected: ‘In previous attempts to investigate human trafficking, we realized that journalists have minimal knowledge about reporting on victims and the legal framework.’

Civil society often tries to raise awareness of issues that place the population at risk. Milan Stefanovic, executive director of PROTECTA, a centre for civil society development in Serbia, believes that loansharking is one potent example of a danger to people’s physical and economic security. Stefanovic says that criminal loansharking is widespread in Serbia, but believes it is not adequately addressed:

Our project on researching and raising awareness of loansharking, supported by the Resilience Fund, is a pioneering endeavour. Based on our television and social-media campaign, around 20 people from Nis and Novi Sad have asked for free legal aid, which PROTECTA offers. Five or six of them are looking for help on loansharking specifically.

Another often neglected societal issue in the region is the reintegration of ex-offenders after serving their terms in prison. On release, they find it challenging to get work, a situation that amplifies their isolation and increases their likelihood of returning to a life of crime. NEOSTART, a centre for crime prevention and post-penal assistance in Serbia, works to help ex-convicts find jobs, which is an essential part of their reintegration into society.

The Belgrade Centre for Security Policy maps non-governmental organizations, investigative journalists and civil society groups in Serbia and Montenegro, with the support of the Resilience Fund. The aim of this interactive service is to promote and increase the visibility of civil society organizations in the Western Balkans 6 that are interested in fighting organized crime.

Although the criminal-justice response in Serbia and Montenegro is mostly focused on crime control, a successful strategy requires prevention, victim support, re-socialization of ex-offenders and external monitoring of the institutional response. In filling this vacuum, these groups have become crucial actors in the fight against crime and corruption.

One of the first steps in building resilience to organized crime is to have ‘a better, more transparent government,’ says Vladimir Otasevic, CEO of the Montenegrin Crime and corruption reporting network LOUPE, in an interview featured in the first issue of the GI-TOC’s Risk Bulletin of the Civil Society Observatory to Counter Organized Crime in South Eastern Europe – a monthly publication that analyzes the risks posed by illicit economies in the region. By building strategies for crime prevention, civil society has the potential to play a more important role in disrupting criminal-governance dynamics in Serbia and Montenegro.

About the author

Sasa Djordjevic joined the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime in September 2020. He is researching organized crime and corruption in the Western Balkans and supports the GI-TOC activities in Serbia and Montenegro. Previously, Sasa worked for almost 12 years as a researcher at the Serbian-based think-tank Belgrade Centre for Security Policy covering police reform, community policing, and hooliganism.