A journey of resilience for the families of Mexico’s missing and slain journalists

Published on April 10, 2020

Griselda’s guests started arriving on a Thursday afternoon. The sheer size and commotion of Mexico City triggered a palpable sense of excitement and amazement among the group arriving in the capital. In the evening, the visitors convened for dinner at the hotel restaurant. Until then, all afternoon their light-hearted conversations had been about their journey to the city. But then Balbina showed up – friendly, but earnest – and the atmosphere turned more sombre, focused. Griselda began to give instructions for the following day’s meeting. ‘They already know your cases,’ she said. ‘So, be clear and precise about your requests.’

When asked whether they wanted to see the prosecutor one by one – to review their cases individually, or to go together – only one favoured going in alone. The others were clear; Frida emphasized the point:

We have come to this moment together, and we’ll go in together.

And so, in between the chats about their meals and travel, one by one they began to outline the details of their sorrows. They spoke about the terrifying possibility of losing everything, of their cases being callously abandoned – and having to fear for their lives. Suddenly, these strong women, who had arrived and greeted me smiling became fragile. And in their tearful eyes, I began to see the stories that Griselda had written in recent months.

Griselda Triana’s husband, journalist Javier Valdez, was murdered in Culiacán, Mexico, on 15 May 2017 outside the office of Riodoce, the newspaper he had co-founded. Griselda has not stopped fighting since. Her quest for justice for the death of the father of her two children has been relentless.

In the days that followed the murder, the federal government had started spying on Griselda and other journalists. The associates of the criminal group that killed her husband continue to operate with impunity in Sinaloa, and Griselda was forced to flee the state with her family. Now she receives protection from armed security offered by a new federal government, and the first sentence for one of the murderers has been handed down. But in Mexico, the path to justice is long and painful.

Even in the midst of her depression and despair, Griselda continues to march on the streets and accepts every invitation to speak for the families of murdered and missing journalists, to defend the freedom of the press, and to denounce the weak level of attention given to victims of violence by the Mexican state.

Griselda has been receiving support from the Global Initiative Resilience Fund since 2019. The project she started up assists the families of murdered and missing journalists in Mexico. She has taken on the task of getting to know these victims, to document their cases and to identify their most pressing needs.

With the support of Claudia Corona, a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Griselda developed a victim-centred methodology to interview these families, who have often been exposed to severe trauma. Her work is also supported through the research and collaboration of Balbina Flores, a representative of Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in Mexico. Balbina has spent many years and travelled long journeys following such cases and visiting these families.

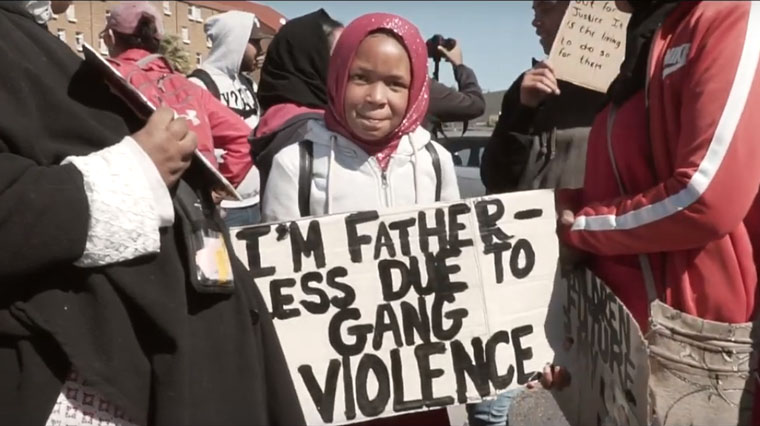

More than 150 cases of assassinated and disappeared journalists have been recorded in Mexico in the last two decades, and the endless number of attacks against the press has intensified in recent years. Impunity for the perpetrators is almost total. The cases recorded by Griselda are filled with stories about displaced families, children who have spent their entire lives looking for their parents and news organizations that have been forced to suppress their coverage on organized crime – or which were forced to shut down because of fear and violence. Meanwhile, the state has been neglectful or incompetent in administering justice – a failure of service that is seen in various state organs and at all levels.

What Griselda has accomplished with the support of her grant and through the efforts of her team, in just a few months of intense work, is no small achievement.

Balbina and Griselda recently organized the abovementioned meeting in Mexico City with the first group of families whom Griselda had interviewed through her work with the Resilience Fund. She had persuaded the federal authorities to receive the families and hear their claims.

Participants travelled from the states of Michoacán and Chiapas to the Mexican capital to insist on the their cases being reviewed, and to demand the protection and reparation measures that each one needs and deserves. They were joined by lawyers from Propuesta Cívica – a civil-society organization that provides legal support to journalists and human-rights defenders. At the meeting, Mexico’s Under Secretary of Human Rights, Alejandro Encinas, pledged to follow up on their demands and promised reparations. At Balbina’s request, a task force was set up between RSF and the Ministry of the Interior to ensure follow-through on these agreements.

After an intense day spent with government civil servants and lawyers, the families gathered again for a resilience-building workshop led by Ana Gladys Vargas, therapist and founder of Tech Palewi – an organization that offers psychological support to victims of violence. Participants were able to reflect on their tragedies together – and to recognize themselves in others who share the same pain. It was also a chance to collectively pause and breathe, and to search among their feelings and thoughts for those that offered them some solace. There were also moments to let go of tears, and spells of laughter.

The night ended with the group embracing one another in memory of Javier Valdez. In the small library that honours his name, where photos of murdered journalists hang from the walls, you could feel the hope and the joy – and the common aspiration that one day, justice will be for all.